Is this love affair headed for destruction?

There is no doubt that we love our automobiles. The earliest models ran on either steam or batteries. Gasoline actually came somewhat later. Why did we switch?

That happened because there is so much energy stored in gasoline. We could drive dozens of miles without having to recharge our batteries or stop to stoke the fire and find more water to make more steam.

Of course it was fantastic to have cars whether they were steam, gasoline, or electric. If you could find a suitable place to get up to speed you could go faster than a horse, and do it continuously, long after a horse would have had to reduce its speed due to exhaustion.

Gasoline just made it more convenient and even more durable. Steam and batteries faded into history.

What goes around…

Now we have finally come full circle, haven’t we? We’re back to electric cars because we’ve created new batteries with large energy densities so that you can drive hundreds of kilometres or miles before you have to find some place to plug in and recharge. The new 100 kW battery pack in the Tesla X P100D will manage 483 kilometres/300 miles on a single charge and manage 0-100 k/h (0-60 mph) in 2.9 seconds.

In many cases we could simply change the battery out and replace it with a fuel cell. Fuel cell systems are smaller and lighter than the heavy membrane-type batteries currently in use.

Of course battery-powered vehicles won’t be replaced by vehicles with fuel cells. The convenience of a battery powered vehicle for people with short commutes is undeniable. They’re clean, green, quiet, and cheap to charge. And right now a kilogram of hydrogen (in this early testing stage) is selling for about US$10 per kilogram (2.2 lbs). The price will come down as our hydrogen infrastructure improves so that it is more comparable with the price of gasoline.

In terms of energy density, a 4 kilogram tank of hydrogen (the normal size for a car) will provide about 500 kilometres (280 miles) of driving, so that would cost you US$40. It can be refilled in just 3–5 minutes, about the same amount of time as filling a car with gasoline.

So now it is fast, comparably priced, and provides a good range for a vehicle…what’s left? Oh yes… the Hindenburg…

Safety

The lighter-than-air craft Hindenburg comes up in almost every conversation about hydrogen. People like to point to the 1937 disaster as an example of how dangerous hydrogen is. The truth is that probably nobody was burned by the hydrogen.

The lighter-than-air craft Hindenburg comes up in almost every conversation about hydrogen. People like to point to the 1937 disaster as an example of how dangerous hydrogen is. The truth is that probably nobody was burned by the hydrogen.

Burns were traced to the aluminiumised fabric of the outer envelope which supposedly protected the ballonets of hydrogen within, and to the spilt and splashed diesel fuel used to power the engines. What most people don’t know is that 61 of the 97 passengers survived.

Despite still being 100 metres/300 feet in the air, the (presumed) lightning strike from the thunderstorm that started the fire in the tail section, allowed the rear section to descend to the ground briskly, but not fatally so. People do not survive a 30-storey drop ordinarily.

The flames quickly flashed the length of the ship as the Hydrogen escaped and burned. To be burned by the hydrogen a person would have to above the gas cells because hydrogen only goes up, never down.

Is It Safe For Cars?

Actually, there’s more stored energy or explosive power in a car’s tank of gasoline than there is a tank of hydrogen. More importantly, gasoline splashes, and pools, and volatises (evaporates) whereas Hydrogen goes straight up.

Actually, there’s more stored energy or explosive power in a car’s tank of gasoline than there is a tank of hydrogen. More importantly, gasoline splashes, and pools, and volatises (evaporates) whereas Hydrogen goes straight up.

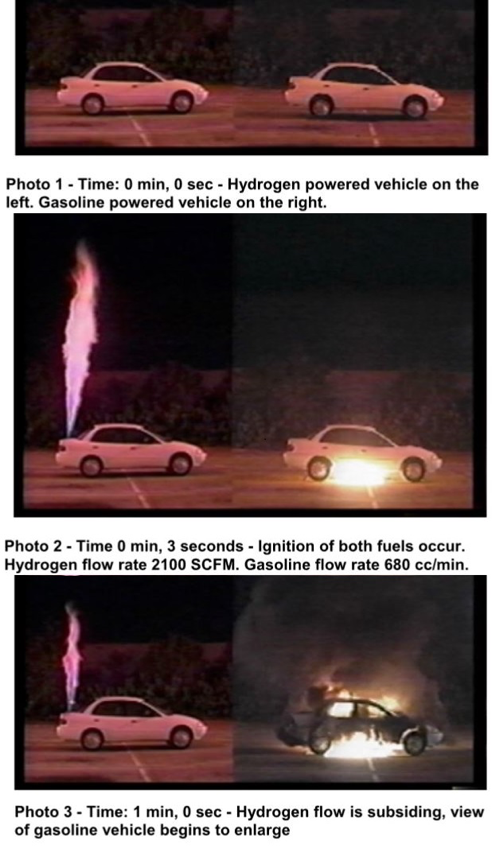

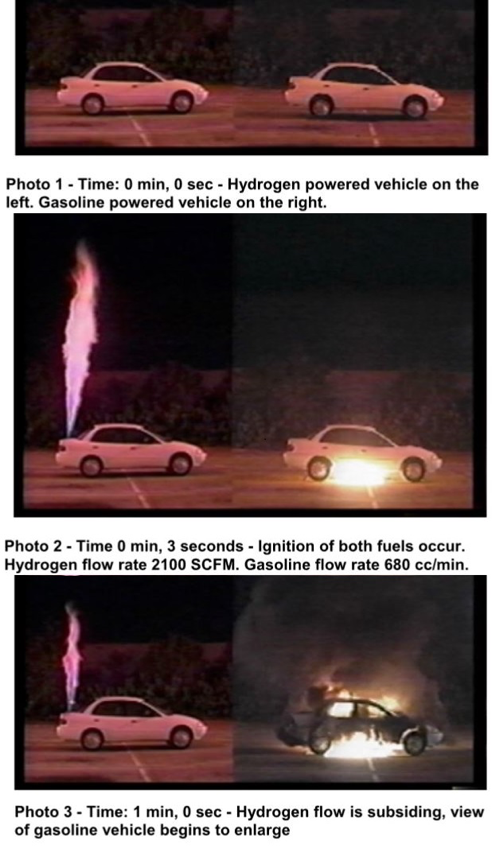

In a study performed by the University of Miami, in 2001, a leak-simulation test was conducted.

As you can see, the gasoline powered car (on the right), was destroyed within a minute. The hydrogen powered car with a leak (on the left) was left completely unharmed. It’s just basic physics: gasoline drips, pools, and collects, awaiting its opportunity to expend all of its stored energy. Hydrogen just wants to escape.

Batteries for electric cars are probably very safe, much like hydrogen. Still, given the choice, I would rather be in an accident with a hydrogen fuelled car, than either a gasoline or battery type. Gasoline is obvious, but a shorted-out battery large enough to power a car could melt and fuse releasing a lot more energy.

The Takeaway

There are a lot of reasons to pick the various types of Power Systems for vehicles. It might be the availability of fuel; how much it cost to move from point A to point B; the environmental impact of your choice; or whether the vehicle has the capability to take you from your point-of-origin to your destination, and then back again, without unnecessary complications about finding fuel.

Within the next few years we will probably phase through from gasoline, to pure electric, and then finally to hydrogen. Good old hydrogen is the most abundant element in the Universe, and aren’t you tired of hearing the same old story about “running out”? Me, too…

External links

National Fuel Cell Research Center

Fueleconomy.gov – page about hydrogen cars

Bilforsikring – Elbil forsikring

Hydrogen Cars Insurance

The Toyota Mirai is a hydrogen fuel cell vehicle that was first introduced to the market in 2014. It is a groundbreaking car that has the potential to revolutionize the way we think about transportation, particularly in terms of reducing greenhouse gas emissions. In this article, we will explore the technology behind the Toyota Mirai and how it works to provide a sustainable and efficient mode of transportation.

The Toyota Mirai is a hydrogen fuel cell vehicle that was first introduced to the market in 2014. It is a groundbreaking car that has the potential to revolutionize the way we think about transportation, particularly in terms of reducing greenhouse gas emissions. In this article, we will explore the technology behind the Toyota Mirai and how it works to provide a sustainable and efficient mode of transportation. The lighter-than-air craft

The lighter-than-air craft  Actually, there’s more stored energy or explosive power in a car’s tank of gasoline than there is a tank of hydrogen. More importantly, gasoline splashes, and pools, and volatises (evaporates) whereas Hydrogen goes straight up.

Actually, there’s more stored energy or explosive power in a car’s tank of gasoline than there is a tank of hydrogen. More importantly, gasoline splashes, and pools, and volatises (evaporates) whereas Hydrogen goes straight up.